|

|

by Ahmar Musti Khan |

|

|

|

No

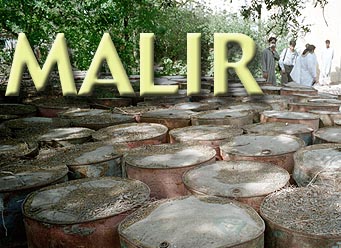

one who enters this courtroom ever forgets it. Not that the cases heard here are remarkable; in this ramshackle building on the outskirts of Pakistan's capitol city of Karachi, the judges rule on routine appeals of prisoners denied bail. What's remarkable is the smell that gags everyone in (or near) the building -- directly outside lies one of the planet's worst toxic garbage dumps.

You first notice the horrible odor nearly a mile away. It comes from piles of industrial 50-gallon drums filled with pesticides that were piled here about a quarter-century ago. The containers have decayed. Some swell like balloons as the deadly chemicals break down into gas; others have burst their lids and their black, greasy contents drip and puddle into the open yard behind this office building. If you dare stand outside for even a few minutes, your eyes water, your head aches, your stomach churns. "We simply can not sit in the courtrooms. The stench is suffocating. Some lawyers [objected when the court was moved here] but the police beat them up and the protest fizzled out," says lawyer Abdur Rashid Shaban. He and the hundreds of other officials, prisoners, lawyers, policemen, plaintiffs and defendants endure the smell, with the small comfort that they can flee after their case is heard. But pity the girls age 4-16 at the school next door, exposed to the toxic fumes daily. Welcome to the infamous Malir dump, one of Asia's worst environmental disasters. |

|

A

physician whose office is near the Malir dump warns that the girls at the adjacent school are particularly at risk of respiratory disease, and that even touching the pesticides could be fatal for them. Some of the expired pesticides were extremely hazardous. One is Kelthane, a member of the DDT family and a potent nerve poison against mites. Kelthane is linked to multiple cancers, birth defects, and endocrine disruption. Another is Gusathion, particularly risky for adolescents and children.

A

physician whose office is near the Malir dump warns that the girls at the adjacent school are particularly at risk of respiratory disease, and that even touching the pesticides could be fatal for them. Some of the expired pesticides were extremely hazardous. One is Kelthane, a member of the DDT family and a potent nerve poison against mites. Kelthane is linked to multiple cancers, birth defects, and endocrine disruption. Another is Gusathion, particularly risky for adolescents and children.

But the horror of Malir is not just this little toxic mountain, with its estimated 4,000 gallons of leaking ooze. Worse is that the dump was once almost one hundred times larger -- and the way the bulk of that pesticide disappeared is still a mystery. The stink and blight has been an ongoing embarassment for the district court, and some of the most visible spills were mopped up by court workers. A watchman at the site points to a batch of newly-emptied drums. "I removed these with my own hands," he said. "Just two days back senior judges of the high court were visiting the premises and we used tractors to pick up the leaking drums and dump them over 100 yards away. There was leakage here, but we put sand on it." Sometimes the toxic goo was dumped into open sewers. Tanvir Arif, founder of the Society for Conservation and Protection of the Environment (SCOPE), a leading Pakistani enviro non-governmental organization, recalls when a water testing project a decade ago. Examining water from 17 wells, they found all of the samples had high pesticide residues and were unfit for human consumption. "The chemical examiners had warned this should never come in the human food chain," he says. But it was mainly thieves who spirited away almost 200 tons of pesticides from the Malir dump. "Over the years, corrupt agriculture officials sold out the pesticides secretly," Arif says. TV producer Shahzeb Jilani, who has long kept a watch on this dump, recalls witnessing what appeared to be one of these black market deals for selling pesticides that were years past their expiration date. "In the dead of night four trucks of the municipal service came and the pesticides were removed from the shed and taken and disposed of at some unknown destination." And once the storage drums were emptied, the real tragedy of Malir begins to unfold, as the barrels were sold to the poor. In Pakistan, where the majority of the population is illiterate, many use these containers for storing essential commodities: wheat flour, rice and "pulses" -- various small beans that form the main diet for the poorest in South Asia. SCOPE founder Arif recalls an incident over a decade ago when his father had brought home an empty pesticide drum from a junk dealer, who probably had bought it from agriculture officials. "There was a little of the chemical still left in the drum, perhaps DDT. My mom spilled it on the floor and for one year after that, any ant or cockroach that dared enter our home died instantly," he says. Writer Jan Khaskheli gives a graphic account of what is happening in the countryside. "I saw children catching fish in a novel method. They had pesticides in their hands and were throwing them into a pond. Quite a few fish died and came on the surface, which the kids took away for their mothers to cook," he said.

|

|

The

pesticide problem began not long after General Ayub Khan siezed control of the Pakistan in a 1958 military coup. "The first batch of pesticides arrived here from the U.S. in the late 1950s, when Washington went out of its way to prop up the government," recalls lawyer Shaban.

Pakistan was not the only country starting to rely upon American pesticides. Many other developing nations were pressured by international aid agencies, pesticide manufacturers, and the U.S. to join the "Green Revolution" that was promised to produce self-sufficiency via chemical-intensive agriculture. Pesticide use exploded thoughout the Third World. By the mid-1980s, India alone had about 200 million acres doused with pesticides -- almost fifteen times the acreage treated twenty years before. Pakistan's next dictator was less keen on the program and stopped subsidizing farmers in the early 1970s, grounding the planes that sprayed the crops. Over the years, the unsold barrels and bags of pesticides were abandonded to the elements in dumps such as Malir, often in heavily populated areas, spread in the length and breadth of Pakistan. Officially called "stores," a study two years ago made a conservative estimate that there were 300 such dumps containing 2000 tons of expired pesticides. Greenpeace made a list of company names on the decaying drums: Takeda Chemicals from Japan, British Petroleum, Dow Chemicals, Sandoz, and Velsicol. Pakistan lacks the ability to do much about cleanup of such a serious toxic problem -- the nation has trouble even coping with standard garbage. Most trash is thrown on open ground or in the waterways. Businesses pollute freely; in the sprawling city of Karachi, only three percent of industries meet international waste treatment standards. There are not even working incinerators for simple medical waste, which brings risk of plague and other contagious disease.

|

|

In July, one huge dump at Jamrud, a city bordering Afghanistan, was safely cleaned. This site had 324 drums of 25 year-old Gusathion and Kelthane. It was a complex deal. Key to helping with the cleanup was Bayer, a multinational company who was a leading maker of the two pesticides. Also involved was the German Agency for Technical Assistance (GTZ), with financial assistance from the Royal Netherlands Embassy. While Bayer agreed to pay the cost of incineration, GTZ paid for handling and shipping the 50 tons of deadly material to England. But even moving the waste to the UK was delayed for months as port authorities struggled to understand a consignment of this nature. As per international convention, a country with no facility to safely destroy obsolete pesticides enters into a contract with the nation that has such a incinerator. The shipment was also conducted in almost complete silence because of fear of enviro protests in all countries involved. "Greenpeace activists do make an issue out of it and could as well block the trans-shipment," explained a friendly staff officer of a Western consulate in Karachi. Yet another major factor was that phenomenal corruption in Pakistan's ministry of food and agriculture. No sooner did the Gusathion and Kaltene leave the Jamrud dump than 400 new barrels of methyl bromide were dumped there, all about to expire within a year. A GTZ spokesman said that the current demand for methyl bromide in the region was just a single barrel a year, illustrating how enormous quantities of pesticides have been forced on nations like Pakistan. Pesticides remain one of the most lucrative businesses in Pakistan; in the last two years, about 45 million tons have been sold, most of it imported. |

|

In

addition to safe pesticide shifting from Jamrud, and the nine dumps in Punjab, there were over 40 tons of expired pesticides at a dump located in a forest that was a wildlife conserve. Amid complaints the dump was playing havoc with the wildlife, the GTZ shifted these barrells to a relatively safer place in another province.

Although 262 tons of obsolete have been shipped out of Pakistan, it represents only about 13 percent of the total known expired pesticide stocks. Obsolete pesticides in private hands, including multinational companies, have yet to be accounted for. "Besides the government-owned stocks of obsolete pesticides, I am told that at least one major private company has built a huge underground tank at its factory to hide off expired pesticides," a diplomat source claimed, on conditions of anonymity. But removing the pesticide alone is not the solution as the story does not end here. "The question of treatment of thousands of contaminated drums and packaging materials has to be solved. A big problem will be the disposal of the large quantities of contaminated soil and cleaning of the stores," according to GTZ expert Wolfgang Schimpf.

Ahmar Musti Khan is an independent journalist and can be reached at: ahmar_reporter@yahoo.com Albion Monitor

February 14, 2001 (http://www.monitor.net/monitor) All Rights Reserved. Contact rights@monitor.net for permission to use in any format. |