Revolving Doors: Monsanto and the Regulators

by Jennifer Ferrara

|

by Jennifer Ferrara |

|

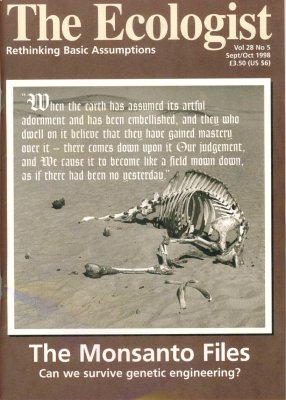

[Editor's note: This article, which is excerpted from Britian's magazine, "The Ecologist," is part of its own controversy about Monsanto and the biotech industry. Last fall, the magazine's printer destroyed all copies because they allegedly feared a lawsuit from the company. Monsanto and the publishers deny that the company told them not print the issue.

[Editor's note: This article, which is excerpted from Britian's magazine, "The Ecologist," is part of its own controversy about Monsanto and the biotech industry. Last fall, the magazine's printer destroyed all copies because they allegedly feared a lawsuit from the company. Monsanto and the publishers deny that the company told them not print the issue.

"We have a long history of being forthright about environmental issues and attacking powerful organizations," says Zac Goldsmith, co-editor of the journal. "Not once, in 29 years, has this printer complained or expressed the slightest qualms about what we were doing." ]

The U.S. was in the heat of a high-tech economic race with Japan, and, as far as agriculture was concerned, lawmakers saw genetic engineering as the new technology that would allow the U.S. to maintain its position as the world's agricultural "leader." The federal government would erect no law that might reduce America's competitiveness in the future world market for bioengineered products.

|

|

The

first government body to establish guidelines for biotechnology research was the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 1976. Since the NIH is an advisory and not a regulatory body, it could formulate guidelines, but it had no power to enforce them. From the beginning, the NIH guidelines relied on the scientific community's and industry's self-regulation, starting a trend that continues today. As corporations became more involved in genetic engineering, NIH guidelines made accommodations for field tests and mass production of genetically engineered organisms. In 1977 and 1978, 16 bills to regulate genetic research were introduced in the U.S. Congress. None was passed, and the NIH guidelines -- which dealt primarily with medical and pharmaceutical research and did not take a precautionary approach -- remained the sole regulatory mechanism for biotechnology research. In the early 1980s, agribusiness corporations were developing genetically engineered plants, animal drugs, and livestock, but no system was in place to regulate the development, sale, or use of these products. This was the era of the deregulatory Reagan/Bush administration, which developed the framework by which bioengineered products, including food, are "regulated" today. Industrial profit, not public safety, was the administration's top priority. Government officials in the Office of Management and Budget, the Departments of State and Commerce, and the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy wanted to ensure that the administration did not do anything to "stifle" the development of biotechnology or to send the "wrong" message to Wall Street. The Bush-era President's Council on Competitiveness, chaired by Vice-President Dan Quayle, joined the biotechnology industry in opposing strong regulations and close oversight by federal agencies. The result was a 1986 "biotechnology regulatory framework." The policy was founded on the corporate-generated assertion that bioengineering was just an extension of traditional plant and animal breeding, and that bioengineered products did not differ fundamentally from non-engineered organisms. The administration determined that existing federal agencies could regulate bioengineered products sufficiently and gave them overlapping regulatory authority. For instance, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) would regulate bio-engineered organisms in food and drugs. The United States Department of Agriculture would regulate genetically engineered crop plants and animals. The Environmental Protection Agency would regulate genetically engineered organisms released into the environment for pest control. And the NIH would look at organisms that could affect public health. In determining that existing agencies could do the job of regulating bioengineered products, the administration avoided passing new, more stringent federal laws or establishing a new regulatory agency devoted to the task.

|

|

The

policy left gaping communication gaps between agencies, plenty of regulatory ground uncovered, and confusion over who would regulate what. But most importantly, the regulations were founded on the false premise that bioengineered organisms used for food and agricultural products are no different from non-engineered, conventional products. In fact, to produce genetically engineered foods, researchers take genes from food or non-food organisms and add them to another organism to alter its genetic makeup in ways not possible through sexual reproduction. The process deletes essential proteins or adds entirely new ones, and can modify genetic characteristics in entirely unexpected ways. As long as the new genes come from an approved food source, the government treats new or altered genes in bioengineered foods as natural, not novel, additives. So in most cases regulators are not required to take a precautionary approach when evaluating new genetically engineered food products; products are considered safe until proven otherwise. As late as 1994, it appeared that the federal government was still playing catch-up in establishing working biotechnology safety regulations. The Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), which monitors the biotechnology industry and the federal regulatory system, was pointing out big holes in the so-called framework." "Fundamentally, it does not contain sufficient statutory authority to oversee all of the products and activities entailed in genetic engineering," wrote UCS in February 1994. "Where authority does exist, there are problems with implementing regulations and policies." For example, a 1992 FDA policy exempted corporations from having to test bioengineered food for safety and get FDA approval before the foods are put on the market. Unless the corporation determined that "sufficient safety questions exist," corporations could undergo voluntary, private "consultations" with the agency before marketing their product. It is not unusual for agribusiness corporations like Monsanto to manipulate the limited safety regulations that exist. To establish safety standards for new products, federal agencies rely on studies performed by the very corporations that are trying to get their products on the market. Studies to determine the long-term health consequences of new products are not always required. Over the years, many corporations have submitted fraudulent test results showing that their products are safe, or they have simply withheld information or studies indicating otherwise. Because the federal government protects corporate safety studies as trade secrets, they are not available for public scrutiny. By sheltering corporations in this way, federal agencies hold corporations' pursuit of profits above the public's right to good health and a safe environment. |

|

Laws

governing biotechnology continue to favor agribusiness and biotechnology corporations, but as the industry has developed, the corporate push for specific types of regulations has taken ironic twists. The initial lack of a cautious regulatory approach enabled small biotechnology companies to develop and market new bioengineered products at a rapid pace. In the meantime, larger agribusiness corporations like Monsanto and Ciba-Geigy were buying up these small companies while developing their own expansive in-house biotechnology research and marketing operations. During this time, Monsanto, Ciba-Geigy, and several other agribusiness corporations came virtually to dominate the world market for bioengineered food products, strengthening their hold over much of the world's food supply. From their position at the top, Monsanto and other corporations have actually favored some seemingly tight regulations, but, it turns out, only when the regulations serve corporate marketing purposes. Regulations that require corporations to submit a plethora of costly scientific data to regulatory agencies, for example, discourage competition from smaller biotechnology and seed companies while giving the public the illusion that new biotechnology products undergo rigorous safety evaluations and are therefore safe. In 1995, for example, Monsanto lobbied against a provision in the EPA funding bill that would have prevented the EPA from regulating agricultural plants bioengineered to contain the toxic bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt). Genetically engineered foods had just hit the market, and Monsanto was fully aware that almost any EPA regulations for Bt plants would publicly sanction the genetically engineered products and defuse resistance from public interest environmental groups. Furthermore, corporations could only get their Bt products to market if they had extensive money and resources to jump through all the regulatory hoops. Big corporations alone can meet data requirements and, once in the system, manipulate and pass the EPA's safety evaluation process. With the competition out of the way, the market is theirs. |

|

|

To

better understand how genetically engineered foods and the associated safety hazards were unleashed upon the American public, take a look at the story of the first mass-marketed bioengineered food product, the Monsanto corporation's recombinant bovine growth hormone (rBGH). rBGH has been linked to cancer in humans and serious health problems in cows, including udder infections and reproductive problems. rBGH's development and approval was rife with scandal and protest. But the right combination of government backing, corporate science, and heavily-funded corporate public relations schemes paved the way for the first major release of a genetically engineered food into the nation's food supply.

The roles played by the FDA and the Monsanto corporation in the development, safety evaluation, approval, and marketing of rBGH led to the exposure of the American public to the multiple hazards of bioengineered foods. These organizations hid important information about safety concens, masked disturbing conflicts of interest, and stifled those who were asking the "wrong" questions and telling the truth about rBGH. The FDA declared rBGH-milk safe for human consumption before important information about how rBGH-milk might affect human health was even available. When critical information about how rBGH raised the levels of insulin-like growth factor, IGF-1, in milk and the possible link between IGF-1 and human cancer began to emerge, the FDA was already apparently in too deep to change its mind or ask more questions about the drug's effect on human health. Instead, the agency relied almost exclusively on data generated by the Monsanto corporation and highly criticized by independent scientists to justify a decision it had made years before. Many independent scientists have called for more extensive, long-term studies, which have never been done. In 1991, a researcher at the University of Vermont, where Monsanto was spending nearly half a million dollars to fund test trials of rBGH, leaked information about severe health problems affecting rBGH-treated cows, including mastitis and deformed births. The scientist heading the research had already made numerous public statements to state lawmakers and the press and released a preliminary report indicating that rBGH-treated cows suffered no abnormal rates of health problems compared with untreated cows. The U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) investigated. During the investigation, the FDA stalled in providing the GAO with original Monsanto test data. and the GAO was unable to obtain critical data from the University and Monsanto. The GAO terminated its investigation, concerned that Monsanto had had time to manipulate the questionable data and that any further investigation would be fruitless. In an effort to dissipate public concern, University of Vermont scientists finally released information showing rBGH's negative effect on cow health, years after the findings had been made. |

|

Even

FDA insiders have criticized the agency for its slack review of the drug, but the FDA has dismissed these concerns and fired at least one official who blew the whistle on the organization's corrupt drug approval process. Veterinarian Dr. Richard Burroughs reviewed animal drug applications at the FDA's Center for Veterinary Sciences from 1979 until he was fired in 1989. In 1985, Burroughs headed the FDA's review of rBGH and remained directly involved in the review process for almost five years. Burroughs wrote the original protocols for animal safety studies and reviewed the data that rBGH developers, including Monsanto, submitted as they carried out safety studies.

A 1991 article in Eating Well magazine quotes Burroughs describing a change in the FDA beginning in the mid-1980s. "There seemed to be a trend in the place toward approval at any price. It went from a university-like setting where there was independent scientific review to an atmosphere of 'approve, approve, approve.'" This is the atmosphere in which the FDA carried out its review of rBGH. According to Burroughs, the FDA was totally unprepared to review rBGH, the first bioengineered animal drug to go through the FDA's approval process; rBGH was out of the scope of most FDA employees' knowledge. But rather than admit incompetence, the FDA "decided to cover up inappropriate studies and decisions," and agency officials "suppressed and manipulated data to cover up their own ignorance and incompetence." Burroughs himself was faced with corporate representatives who wanted the agency to ease strict safety testing protocols, and he saw corporations drop sick cows from rBGH test trials and manipulate data in other ways to make health and safety problems disappear. According to Burroughs, the raw, untouched data stashed away behind the agency's doors and protected as trade secrets would show otherwise. Burroughs challenged the agency's lenience and its changing role from guardian of public health to protector of corporate profits. He criticized the FDA and its handling of rBGH in statements to Congressional investigators, in testimony to state legislatures, and to the press. Inside the FDA, he rejected a number of corporate-sponsored safety studies as insufficient and was prevented by his superiors from investigating data submitted by industry revealing possible health problems caused by rBGH. Though Burroughs had a record at the FDA showing eight straight years of good performance, he began receiving poor performance reports, for which he claims he was set up. Finally, in November 1989, he was fired for "incompetence." Not only did the FDA fail to act upon evidence that rBGH was not safe, the agency actually promoted the Monsanto corporation's product before and after the drug's approval. In doing so, the FDA took on the impossible double role of regulator and promoter of bioengineered foods. Dr. Michael Hansen of Consumers Union notes that the FDA acted as an rBGH advocate by issuing news releases promoting rBGH, making public statements praising the drug, and writing promotional pieces about rBGH in the agency's publication, FDA Consume. This dual role also manifested itself in other ways. In an apparent attempt to quell public controversy over rBGH, for example, two FDA researchers published industry and "independent" data in the journal Science in 1990 to show that rBGH was safe for consumers. Gerald Guest, the director for FDA's Center for Veterinary Medicine told Science, "We'd like to get our side of the story out, to show why we're comfortable with the safety. We'd like for people to know that ifs a thoughtful process. and we want it to be open and credible." Guest was apparently doing a lot of wishful thinking. Professor Samuel Epstein criticized the FDA for acting "as a booster or advocate for an animal drug that hasn't yet been approved." Epstein and others faulted the FDA for including only pieces of unpublished studies about rBGH in the Science article, but not making the full studies available for independent review. |

|

The

FDA's pro-rBGH activities make more sense in light of conflicts of interest between the FDA and the Monsanto corporation. Michael R. Taylor, the FDA's deputy commissioner for policy, wrote the FDA's rBGH labelling guidelines. The guidelines, announced in February 1994, virtually prohibited dairy corporations from making any real distinction between products produced with and without rBGH. To keep rBGH-milk from being "stigmatized" in the marketplace, the FDA announced that labels on non-rBGH products must state that there is no difference between rBGH and the naturally occurring hormone.

In March 1994, Taylor was publicly exposed as a former lawyer for the Monsanto corporation for seven years. While working for Monsanto, Taylor had prepared a memo for the company as to whether or not it would be constitutional for states to erect labelling laws concerning rBGH dairy products. In other words. Taylor helped Monsanto figure out whether or not the corporation could sue states or companies that wanted to tell the public that their products were free of Monsanto's drug. Taylor wasn't the only FDA official involved in rBGI-1 policy who had worked for Monsanto. Margaret Miller, deputy director of the FDA's Office of New Animal Drugs was a former Monsanto research scientist who had worked on Monsanto's rBGH safety studies up until 1989. Suzanne Sechen was a primary reviewer for rBGH in the Office of New Animal Drugs between 1988 and 1990. Before coming to the FDA. she had done research for several Monsanto-funded rBGH studies as a graduate student at Cornell University. Her professor was one of Monsanto's university consultants and a known rBGH promoter. Remarkably. the GAO determined in a 1994 investigation that these officials' former association with the Monsanto corporation did not pose a conflict of interest. But for those concerned about the health and environmental hazards of genetic engineering, the revolving door between the biotechnology industry and federal regulating agencies is a serious cause for concern.

Reprinted by special permission Albion Monitor

May 7, 1999 (http://www.monitor.net/monitor) All Rights Reserved. Contact rights@monitor.net for permission to use in any format. |